Connecticut high schooler Betty Berdan summarized one of the most common positions against the Millennial generation in her opinion piece for The New York Times, writing: “When awards are handed out like candy to every child who participates, they diminish in value.”

She adds: “Trophies for all convey an inaccurate and potentially dangerous life message to children: We are all winners.”

Berdan’s (and virtually everyone else’s) argument goes on to say that not everyone is a winner in real life. Simply showing up does not merit a reward, let alone celebration. In the real world, there are winners and losers. Except instead of trophies and ribbons, the winners get financial security, and the losers do not.

But the number of losers, as well as the divide that separates them from the winners, are growing at an alarming rate. This is what makes the Millennial challenge unique, and it’s what makes the generational disdain unjustifiable.

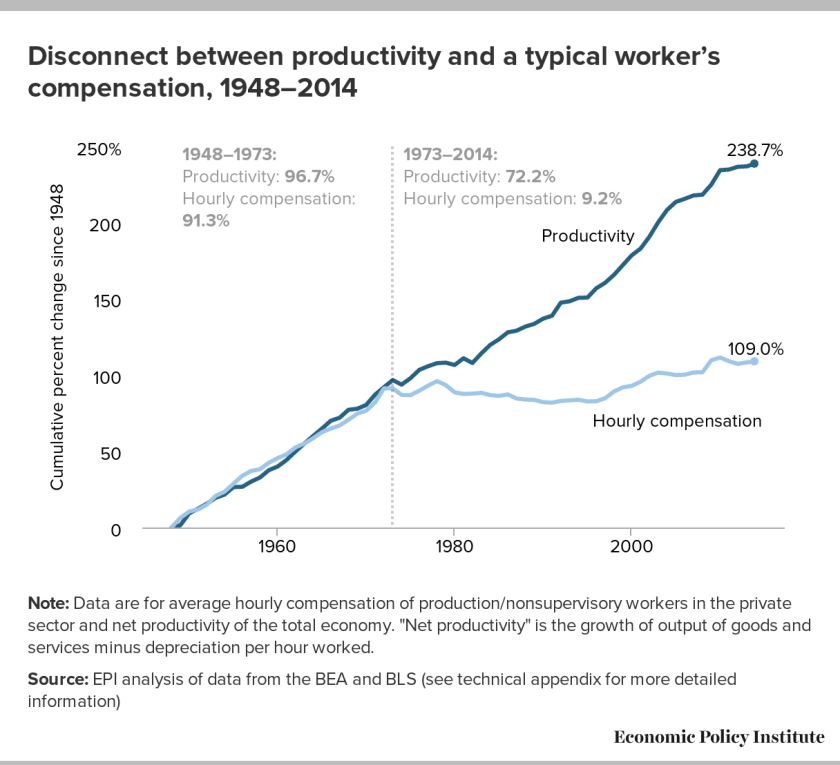

There is perhaps no greater indicator of increasing hardships on the Millennial generation than the comparison between productivity and hourly wages. From 1948-73, the two rose in almost perfect tandem. But starting in the ’70s, one began veering more sharply while the other continued its climb. The result: From 1973-2014, as Washington began deregulating and privatizing the economy, worker productivity rose 72.2 percent, but hourly compensation lagged behind at 9.2 percent.

To be clear, this is not an issue that’s affecting only those in their 20s and 30s. Working class Americans have been dealing with wage stagnation for decades. But worker productivity is not tailing off. We’re creating more profit than ever before. So when The New York Times prints headlines like “The Economy Is Looking Awfully Strong,” one is left to wonder: Who’s reaping the benefits?

When the Trump administration pushed tax reform through Congress in December, the promises included higher pay, more jobs and more investment by companies. It was no surprise to see corporate media rolling out what essentially amounted to free PR work for the administration as companies began announcing bonuses and wage increases.

But a Washington Post analysis showed that for every $1 major companies are spending on bonuses and wage increases, they are spending $30 to buy back their own stocks, benefiting shareholders and raising the pay of chief executives. A survey of Morgan Stanley analysts found that 43 percent of companies’ tax cut savings will go to investors in the form of “stock buybacks and dividends,” and 13 percent will go to “pay raises, bonuses and employee benefits.” That’s deeply troubling considering we’re already slogging through mud.

An investigation by The Guardian found, in part, that Americans under 30 are now poorer than retired people. They also have less disposable income than people aged 65-79, which is the first time that’s happened as far back as the analyzed data go. It’s worth repeating the oft-cited study that shows Millennials may very well be the first generation to earn less than previous generations.

This will only serve to exacerbate the issue of a growing split between America’s financial winners and losers.

The vast divide between the wealthiest and everyone else has been a central talking point in this country since the last presidential primary season, and the attention is mostly thanks to Bernie Sanders, who made it a theme in his run for president. The “1 percent” talking point is extremely important. Those folks at the top own 40 percent of the country’s wealth, which is as high as it’s been at any point since at least 1962.

This is an appropriate time to turn back that New York Times opinion piece. The final sentence: “[I]t is fact that there’s room for only a select few on the winners’ podium.”

A select few, indeed.

A popular remedy to this American fault is college. We’re conditioned from an early age to constantly be worried about our marketability to universities and, one day, employers. This takes away a great deal from childhood, though. One of the great and obvious impacts is that kids aren’t, well, being kids as often anymore. After all, what’s the point of playing with friends if you could be getting a head start on studying for the PSAT? If you’re not doing it, someone else is, and they might beat you out for that competitive college slot.

Still, young workers today are more likely than any previous generation to have a Bachelor’s degree. Forty percent of Millennials are college graduates, compared to 32 percent of Xers and 26 percent of Boomers. More Americans accruing student loan debt is likely a contributing factor to why Millennials are earning 20 percent less than Boomers did at the same stage in life.

Students are being tasked with increasingly steeper prices that would drive consumers away from virtually any other product. Over the past 30 years, the cost of attendance has shot up around 220 percent, and it doesn’t matter if you’re looking at public or private universities.

How are we paying for rising costs? Working and borrowing more. A 2015 Georgetown University study found that more than 70 percent of college students are working, a trend that has been steady for the past 25 years. What’s more, around 40 percent of undergraduate students work 30 or more hours per week. With the average cost of attendance at in-state public schools being around $25,000 per year, “working learners” would need to work 66 hours per week at minimum wage (before taxes) to cover those costs. Needless to say, it’s uncommon. Instead, we turn to student loans.

The Student Loan Debt Clock shows $1.5 trillion in loan debt. Those who graduated in 2016 had an average of $37,172 in debt. For comparison, graduates in the early 1990s walked away with an average of $10,000 in loan debt, meaning that number has more than tripled in less than three decades.

In other words, investing in your own human capital is becoming a dangerously unstable practice, and that’s even without approaching college as a formative experience. Of course, it’s common to hear people say it’s wiser to pursue a trade instead of going to college, but automation is presenting an increasing threat to the American (and global) workforce. A study by the McKinsey Global Institute concluded that one-third of workers in richer countries like the United States could be displaced by 2030. Automation is on track to bully workers across a wide range of industries and professions, college degree in hand or not. The jobs that will stay safest the longest are highly skilled occupations like substance abuse social workers, surgeons and teachers. And just because a job (material movers, for example) is relatively safe from automation doesn’t mean it’s safe from everyone else who does get displaced and has to find a new job.

The solutions to our problems unfortunately don’t seem to be coming to shore. Trump takes the heat here only because he’s president. What if Hillary Clinton had won? Big banks would still be deregulated, health care premiums would keep rising. We would still be, in a word, screwed.

Which circles us back to the participation trophy dilemma. If you’re not bothered by poverty, a student debt crisis and growing wealth inequality, then arguing that 10-year-old softball players shouldn’t get participation trophies is true to character. In fact, it should only be the pitcher and catcher of the championship team who get trophies. Everyone else will drag the infield and clean the dugouts.

These times in childhood where we do want to recognize and congratulate kids for having fun, working hard, being part of a team—why can’t they be used to show the child what a more just society might look like? Instead of being hellbent on revealing to every kid how much life is going to suck, why not offer a glimpse of how it can be improved?